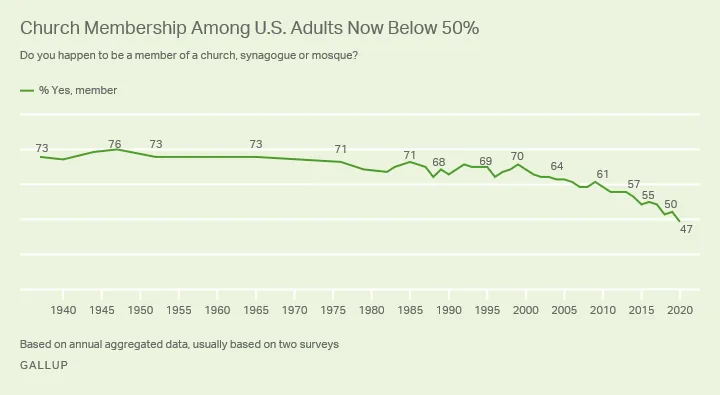

About a month ago, Gallup published new research showing that, for the first time, the percentage of Americans who are church members fell below 50%.

This, by itself, may not be too surprising. Many of us have some general awareness that American culture is less religious than it used to be. What’s really surprising is how quickly it’s happened:

What’s going on? What changed in 2000 (to pick a nice round number) to cause the rate of decline to accelerate so much?

I’m not a sociologist or a professional minister; there are others who are better qualified to speak than I. But, looking at that chart, I’m reminded of a quote from Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises:

“How did you go bankrupt?”

“Two ways. Gradually, then suddenly.”

This is one of those pithy, attention-grabbing quotes that seems contradictory but, upon reflection, contains a lot of truth. Because that’s often how bankruptcy works - a household or a business may be able to continue for quite a while living just a bit beyond their means, making the minimum credit card payments, or with expenses gradually creeping up while sales gradually creep down. Then something hits - there’s an unexpected medical expense or costly repair, or one too many late payments cause fees and penalties to snowball, or an economic dip or competitive pressure suddenly makes the fragile business unsustainable - and bankruptcy occurs seemingly all at once.

Looking at that Gallup chart, I can’t help but think that something similar happened here. A healthy, vibrant church, full of active, committed Christians, doesn’t simply have its membership plummet in less than a single generation; I can’t help but wonder what kind of gradually-then-suddenly scenario American Christendom has been going through, what weaknesses we’ve allowed to fester and grow until our position became untenable in the face of a worldly culture.

It’s easy to guess at what those weaknesses might be. I suspect that part of the decline is because we’ve too uncritically allied ourselves with particular political agendas and a particular political party; even when those causes have been good, it’s hard to maintain our distinctiveness when the broader culture sees us as yet another political interest group. Russell Moore writes:

Even as a teenager, I could see that the “voting guides” that showed up in Bible Belt America were kind of like the horoscopes one could find in the newspaper. The horoscope could say, “Today you will find a surprising new opportunity,” and a certain sort of credulous person would be amazed at how this just happened to be true—without ever thinking about the fact that this is true of virtually every human being at virtually every moment, if one just pays attention to it. Likewise, the voter guides lined out the “Christian” view from the “anti-Christian view” on a list of issues that just happened to line up with the favored party’s platform that year. Somehow the Bible suddenly gave us a “Christian view” on a balanced budget amendment or a line-item veto, things that… were never noticed in the text until the favored candidates started emphasizing such things.

And along with all that came apocalyptic warnings that if these candidates weren’t elected, or these policies weren’t enacted, we would “lose our entire culture.” But when those candidates lost, no one headed for the bunkers. The culture didn’t fall—at least not any more than it had before.

The sad fact is that, for many Americans, the only experience they have with evangelicals is at a distance, as their opponents at the ballot box. To borrow from Philip Yancey and Gregory Boyd, it’s incredibly difficult to extend grace to people when you’re also trying to defeat them politically; it’s hard to advance both the kingdom of the cross (which transforms people from the inside) and an earthly government (which can merely compel external behavior).

I suspect that part of the decline of the American church is because we’ve allowed moralism and legalism to be portrayed as key parts of Christianity. This shows up in a variety of ways - an emphasis on “obvious” sins like sexual immorality, alcoholism, and drug addiction instead of subtler sins like pride and dishonesty and bitterness, as well as picking out everything from R-rated movies to teetotaling to particular styles of clothing to Dungeons & Dragons to violent video games as vital moral issues. Please don’t misunderstand me. Morality - trying to live a life pleasing to our Creator, following the way he wants us to live - is obviously incredibly important. And I love that my brothers and sisters have been trying to apply God’s standards to every facet of their lives - R-rated movies and teatotalling and the rest - because examining every facet of our lives and living with a clear conscience is also part of trying to live a life pleasing to our Creator. I’m even in agreement on a decent amount of this. But the problem comes when we set up these as a central aspect of the faith, rather than our best human effort to live out our faith; people mistake the legalism for the Gospel and walk away from it all, or they see the inconsistencies in our causes or the flawed, human, sometimes arbitrary morality (because we’re all flawed and human and sometimes arbitrary) and think that the whole of the faith is that. In The Life You’ve Always Wanted, John Ortberg suggests that part of the problem is that we let these moral issues become “boundary markers” - “highly visible, relatively superficial practices - matters of vocabulary or dress or style - whose purpose is to distinguish between those inside a group and those who are outside”:

The church I grew up in was a fine church, and I am deeply in its dept, but we also had our own set of markers there. The senior pastor could have been consumed with pride or resentment, but as long as his preaching was orthodox and the church was growing, his job would probably not be in jeopardy. But if some Sunday morning he had been smoking a cigarette while greeting people after the service, he would not have been around for the evening service. Why? No one at the church would have said that smoking a single Camel was a worse sin than a life consumed by pride and resentment. But for us, cigarette-smoking became an identity marker. It was one of the ways we were able to tell the sheep from the goats…

A boundary-oriented approach to spirituality focuses on people’s position: Are you inside or outside the group? A great deal of energy is spent clarifying what counts as a boundary marker.

But Jesus consistently focused on people’s center. Are they oriented and moving toward the center of spiritual life (love of God and people), or are they moving away from it? (p. 34-37)

I suspect that part of the decline is specific sins that we’ve allowed within the church: the racism of the American south, sexual abuse within the Catholic priesthood and other churches, financial exploitation by televangelists and others. The sad fact is that we have a lot to answer for here. White southern evangelicals did little to help the civil rights movement, and many of our private Christian schools in the south were founded in the wake of Brown v. Board of Education by whites who wanted an alternative to the newly desegregated public schools. Sexual abuse by religious leaders and organizations from Catholic priests to Ravi Zacharias to Kamp Kanakuk have done grievous harm; organizations frequently chose to protect themselves or the perpetrator (for example, by trying to handle it internally) rather than prioritizing bringing justice for the victim, and Christian teachings such as Bill Gothard’s downplayed the harm and blamed the victims (before Gothard himself was accused of repeated sexual harassment). Christian leaders such as Jim Bakker, Jimmy Swaggart, Ted Haggard, and Jerry Falwell Jr. have all had heavily publicized scandals. These aren’t just “a few bad apples”; I’ve read too many accounts of racism, of theology that’s abused to excuse sexual sin, of a willingness to overlook warning signs if a ministry is successful, of preying on people’s political fears or luring them with health-and-wealth. We need to repent. Now, especially, when the broader American culture is seriously confronting sexual harassment and abuse and America’s history of racism - through some mix of God’s common grace and fallen human moralism - the church’s failings in these areas become even more glaring. I’m afraid that we at times even let attitudes on race and sex become boundary markers themselves - “secular progressives are emphasizing these things, so we’re instead going to de-emphasize them, because those guys are our enemies.” This should not be.

And I suspect that part of the decline may be that some of the church membership and church activities from 2000 and earlier was, in fact, just going through the motions. In a 2014 column, Ross Douthat suggests that we’re seeing “the Christian Penumbra”:

Here is a seeming paradox of American life. One the one hand, there is a broad social-science correlation between religious faith and various social goods — health and happiness, upward mobility, social trust, charitable work and civic participation.

Yet at the same time, some of the most religious areas of the country — the Bible Belt, the deepest South — struggle mightily with poverty, poor health, political corruption and social disarray…

The social goods associated with faith flow almost exclusively from religious participation, not from affiliation or nominal belief. And where practice ceases or diminishes, in what you might call America’s “Christian penumbra,” the remaining residue of religion can be socially damaging instead…

It isn’t hard to see why this might be. In the Christian penumbra, certain religious expectations could endure (a bias toward early marriage, for instance) without support networks for people struggling to live up to them. Or specific moral ideas could still have purchase without being embedded in a plausible life script. (For instance, residual pro-life sentiment could increase out-of-wedlock births.) Or religious impulses could survive in dark forms rather than positive ones — leaving structures of hypocrisy intact and ratifying social hierarchies, without inculcating virtue, charity or responsibility.

And it isn’t hard to see places in American life where these patterns could be at work. Among those working-class whites whose identification with Christianity is mostly a form of identity politics, for instance. Or among second-generation Hispanic immigrants who have drifted from their ancestral Catholicism. Or in African-American communities where the church is respected as an institution without attracting many young men on Sunday morning.

Several Christian leaders have suggested that religious faith within a family follows a regular pattern: The initial converts of the first generation are active and passionate in their faith. Their children, the second generation, inherit their parents’ faith; they’re still active, and their faith is still meaningful, but they lack the firsthand commitment and passion of their parents. As a result, in the third generation, religion is more of a formality, just going through the motions. The fourth generation then leaves the faith completely.

All of this is, of course, a generalization; every family is unique, and plenty of families (including my own!) have a powerful, multi-generational legacy of faith. But it’s a penetrating illustration. I suspect that much of church membership has been these “third-generation Christians,” going through the motions, and what shows up in the polls as church decline is merely the next step of the decay. The remedy is for each generation to be the first: each new generation of Christians must make that personal, passionate, first-hand commitment for themselves.

I grieve over the American church’s decline. I love the church, and I believe that it can offer enormous good; I love Christ, and I want people to know him. But, if what I said is accurate, if what we’re seeing is the merely the next step of the Christian penumbra and nominal third-generation faith, then it may not even be a bad thing. C.S. Lewis observes in Mere Christianity, “When a young man who has been going to church in a routine way honestly realises that he does not believe in Christianity and stops going-provided he does it for honesty’s sake and not just to annoy his parents-the spirit of Christ is probably nearer to him then than it ever was before.” Christian novelist Leif Enger writes,

If I may offer a perspective on the church ‘losing a generation,’ it’s worth considering that widespread disillusionment with evangelicalism is largely a positive development. I can’t speak for a soul outside my experience, but as the product of Midwestern charismatics who subscribed early to Fox News and never looked back, I suspect the progression from Falwell Sr. to Falwell Jr. applies more broadly than any of us care to imagine. A teen who sees through the rot and ‘falls away’ remains as available to the Creator as any prodigal in history; those who remain despite the rot will learn to tolerate it, follow it, and finally exalt it. This is predictable and proven before our eyes. At this fraught moment it’s the non-skeptics I dread.

God is still at work, in his church and in the world. The story isn’t over yet, not for the individuals whose decisions make up the decline or for the American church as a whole. Church attendance numbers and cultural influence are nice, but the point is following Christ. The Gallup polls show a snapshot in time, but we know that ultimately the gates of hell will not prevail and every knee shall bow (Matt. 16:18, Phil. 2:10).

So let’s re-center our lives and our faith on Christ and his kingdom, not on political causes.

Let our morality flow out of following Christ, rather than being a legalistic cause and identity marker.

Confront and repent of our sin.

Commit to Christ, and teach our children to do the same.

Further reading:

- Russell Moore’s “Losing Our Religion” wrestles with the Gallup poll’s findings and presents his personal perspective, and David French presents an Easter meditation on it.

- Rachael Denhollander is doing critically important work on sexual abuse within the church. Her Twitter feed and her husband’s are good (and sad) reading. (I first heard about her when she extended the Gospel to her abuser, former USA Gymnastics team doctor, Larry Nassar, in courtroom testimony.)