I was recently deeply moved by a song: it spoke to the frustrations and tensions of being both an American and a Christian, the sadness of seeing religion exploited for power, grief over the suffering of those around us, and the need to love others. I thought about sharing it online, but it makes reference to current political issues, so I didn’t, for fear that it seems like I’m taking sides in a controversy – we could all find agreement with its basic message, yet I feel like I’d have to post a disclaimer if I posted a link to the song.1 “Regardless of your stance on this issue, I think Christians can…”

I have an entire shelf full of Christian books that have significantly impacted my life but whose authors have gone astray, fallen, or embraced questionable beliefs. Now I’m afraid to cite them; do I need to preface each quote with a warning? “Although I don’t endorse everything this author has done, he was right when he said…”

I recently saw an article by a Christian theologian I respect. He quoted a writer who’s made decisions I believe to be wrong. I found myself annoyed that there was no qualifier; it left me wondering whether he endorses the writer’s actions. Why can’t he reassure me that he agrees with me? “Even though I’m quoting him, I don’t agree with…”

I recently shared with some friends a matter that was important to me. Because it touched on a current political topic, the discussion quickly turned to argument. With some effort, we wrestled the discussion back to an agreement that we should be able to share matters on our heart – and, perhaps, a nonverbal agreement that we would never speak of that specific matter again, lest we cause more conflict. “This is important, but we don’t expect…”

At a church group, a social issue came up. I don’t think we disagreed with what we should do about the need, but an argument arose over how we thought about what we should do about the need, and whether what we thought was slipping toward what certain secular groups thought, and whether it therefore needed to be opposed. Would a disavowal have helped there? “Obviously, I don’t endorse what these groups are claiming, but…”

It’s a weird state of affairs. We don’t expect this behavior when we read the Bible; it would be strange if we came across it. Can you imagine Jesus doing this in his debates with the Pharisees (Mt. 22:41-45)?

Jesus asked them a question: “What do you think about the Christ? Whose son is he?” They said, “The son of David.” He said to them, “How then does David by the Spirit call him ‘Lord,’ saying,

“‘The Lord said to my lord, “Sit at my right hand, until I put your enemies under your feet”’?

“Truly I tell you, I say this not to praise everything David did, for David committed adultery and murder and, it is argued by some, even forced himself upon Bathsheba.”

Or imagine Paul in Athens (Acts 17:22-23):

So Paul stood before the Areopagus and said, “Men of Athens, I see that you are very religious in all respects. For as I went around and observed closely your objects of worship, I even found an altar with this inscription: ‘To an unknown god.’ Therefore what you worship without knowing it, this I proclaim to you. But, before I can do that, I must explain that your objects of worship are false gods, powerless, and an offense to the God who gives life and breath and everything to everyone, and that even your altar to an unknown god does not follow the commandments of worship that God gave his people. After all, I cannot allow it to look as though I am soft on idolatry.

Or if the author of Hebrews wrote like this (Heb. 11:7-10):

By faith Noah, when he was warned about things not yet seen, with reverent regard constructed an ark for the deliverance of his family. Through faith he condemned the world and became an heir of the righteousness that comes by faith. Although we should not forget that he then got drunk and was humiliated by his son. By faith Abraham, obeyed when he was called to go out to a place he would later receive as an inheritance, and he went out without understanding where he was going. Without faith he lied about his wife to Pharaoh and Abimelech and took matters into his own hands, making Hagar his concubine.

And we generally avoid it with figures from our more recent national histories. For the recent celebration of Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday, people talk about the stirring moral vision of “I Have a Dream” and the arc of the universe bending toward justice; the passionate yearning for equality expressed in “Letter from a Birmingham Jail”; the union of unyielding courage and uncompromising love for his enemies that led to his commitment to nonviolent resistance. Less commonly discussed is his much more controversial commitment to socialism; his alleged extramarital affairs or his plagiarism are hardly even mentioned. Soon, we’ll celebrate George Washington’s birthday. We2 have no difficulty honoring him for his integrity and humility, his canny leadership, his willingness to renounce power, and his influence on our country, without worrying that we’re excusing his slaveholding.

Why is it different with the issues that trouble us today?

Some of it comes from a good place: out of a pastoral concern for brothers and sisters who may be less mature or less informed in their faith, we want to point out the potholes and pitfalls along the way, to remind them that thinkers and schools of thought may contain bad as well as good, to prepare them so they won’t be disillusioned by the dismal reminders that even spiritual leaders remain sinners.

Some of it comes from an effort to have right priorities: if we really do love God with all our heart, soul, mind, and strength, if there is no square inch over which Christ does not cry, “Mine!”, then we don’t want to excuse sin, and we want to extend that Lordship over political and social issues and theological debates. We wouldn’t want to overlook or downplay moral failings or flawed thinking, any more than an athlete would overlook training gaps or bad technique, or a soldier would overlook damaged or deficient gear. And some of it is a sincere realization that actions and thoughts have consequences, that sinful actions and wrong ideas both can have a corrupting influence on ourselves and others, leading us astray sometimes subtly and sometimes with deadly effect.

But some of it comes from less commendable places. My hesitancy around political issues or sharing concerns with my friends reflects a fear of argument and disunity. But we are brothers and sisters in Christ, united into the family of God by the one who “is our peace,” who “destroyed the middle wall of partition, the hostility” of millennia-old divisions (Eph. 2:14-16), through his blood on the cross. How do we let mere human issues or arguments damage that? I want to see theologians’ disclaimers, not because of my overriding concern that they extend Christ’s Lordship over their thinking, but because I want the reassurance that they’re on my side, that my viewpoint is right and respectable and widely held. In various corners of the Internet, one can easily find professing Christians whose primary online activity seems to be telling other professing Christians about all the flaws in their doctrine and all the ways in which they’re compromising with the world. It doesn’t come across as pastoral concern; it doesn’t seem like they’re ruthlessly training or honing their spiritual gear. It comes across as reinforcing their own rightness by saying that others are out, or honing their rhetoric and doctrine at the cost of tearing others down, or maybe just increasing their cachet among their social media followers.

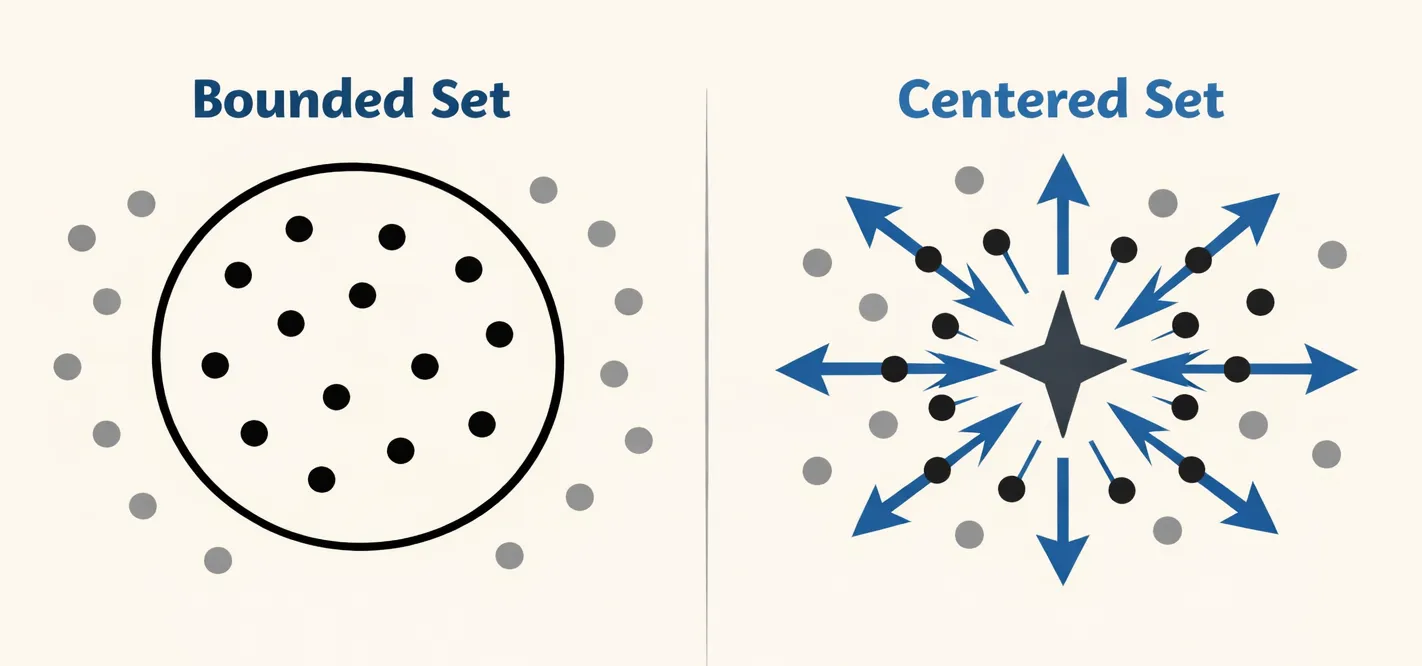

Some of our behavior, ironically, comes from wrong priorities. Missiologist and anthropologist Paul Hiebert talks about bounded sets versus centered sets. In a bounded set, the focus is on the group’s boundaries: who’s in and who’s out, what characteristics or behavioral markers or beliefs can be used to identify that boundary. In a centered set, the focus is on the group’s center and goal. Where individuals currently stand is less important than whether they’re moving toward the goal. If we stay focused on Christ, then we can rejoice when others are moving toward him, even if they’re currently far from us; if we’re focused on the boundaries, then by definition we’re not focused on Christ.

Some of our disapprovals and disavowals are because none of us are abstract and idealized followers of Christ: our beliefs and ideas are complex bundles of upbringing and culture and sanctification and rationalization. As such, we can’t help but sometimes view disagreement with our beliefs – the existence of opposing viewpoints – as attacks on us, so we throw up disclaimers and qualifications to protect ourselves, rather than face the discomfort that we might be wrong.

And some of it, I fear, is pure partisanship. We correctly realize that we’re in a spiritual war but forget who we’re fighting:3 having come to view our enemies as flesh and blood, we start to view our task as identifying who’s in and who’s out, who’s on our side and who isn’t. If we’re in a war, then we fear losing, so we hunt down and call out any weakness or deviation. If the enemy is out there, then we need to build up our walls, man the watch posts, be ever vigilant.

But if, as Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn said, “The line separating good and evil passes not through states, nor between classes, nor between political parties either – but right through every human heart” – and I believe this is the more Christian view – if we’re all made in God’s image and fallen, if all believers are sinners saved and sanctified, then we’re freed from this. We can commend the good wherever we find it, because we recognize that all are made in God’s image and capable of good, and we want to use whatever good we can to give honor to God and point people to him. We can call out the bad wherever we find it, not from a position of superiority, but from a position of coming alongside and calling toward our common goal. We can stop worrying so much about accidentally endorsing what’s bad, because we aren’t surprised to find what’s bad, because we recognize that we all fall short. (Bonhoeffer, Life Together: “Anybody who lives beneath the Cross and who has discerned in the Cross of Jesus the utter wickedness of all men and of his own heart will find there is no sin that can ever be alien to him. Anybody who has once been horrified by the dreadfulness of his own sin that nailed Jesus to the Cross will no longer be horrified by even the rankest sins of a brother.”) We can trust in the Holy Spirit to guide and protect us as we seek to follow Christ, instead of being afraid of falling prey to corruption.

Paul is perhaps my favorite example of this. In his own life, he set ruthlessly demanding standards: “I subdue my body and make it my slave, so that after preaching to others I myself will not be disqualified” (1 Cor 9:27). “I have great sorrow and unceasing anguish in my heart. For I could wish that I myself were accursed—cut off from Christ—for the sake of my people” (Rom 9:2-3). “I am even more so” “a servant of Christ,” “with much greater labors, with far more imprisonments, with more severe beatings, facing death many times… Apart from other things, there is the daily pressure on me of my anxious concern for all the churches” (2 Cor 11:23,28). “I now regard all things as liabilities compared to the far greater value of knowing Christ Jesus my Lord, for whom I have suffered the loss of all things —indeed, I regard them as dung!” (Phil 3:8).

Yet, for the people he ministered to – those who pressured him daily with anxious concern, those for whom he could wish himself accursed – he demonstrated an expansiveness, a graciousness. Even while he exhorted them to follow Christ, even when he called them out for their shortcomings, he demonstrated a kind of settled confidence that God would take care of them. For example, in Philippians 3:13-15 (ESV), after laying out his all-consuming drive to know Christ, he concludes:

One thing I do: forgetting what lies behind and straining forward to what lies ahead, I press on toward the goal for the prize of the upward call of God in Christ Jesus. Let those of us who are mature think this way, and if in anything you think otherwise, God will reveal that also to you. (emphasis added)

Or Philippians 1:6 and Philippians 2:12-13:

For I am sure of this very thing, that the one who began a good work in you will perfect it until the day of Christ Jesus.

Continue working out your salvation with awe and reverence, for the one bringing forth in you both the desire and the effort—for the sake of his good pleasure—is God.

Or Romans 14:4, in the context of one of these debatable theological issues:

Who are you to pass judgment on another’s servant? Before his own master he stands or falls. And he will stand, for the Lord is able to make him stand. (emphasis added)

“For everything belongs to you, whether Paul or Apollos or Cephas or the world or life or death or the present or the future. Everything belongs to you, and you belong to Christ, and Christ belongs to God” (1 Cor 3:21-23).

Footnotes

-

The song is Jon Guerra’s “Citizens.” It’s rapidly become one of my favorites. ↩

-

Peter Kreeft, writing from a demon’s perspective in The Snakebite Letters:

↩If there’s a war, there must be an enemy. Who do they think their enemy is? There are only four possibilities.

- They often used to believe their enemies were concrete human beings. This lie was extremely useful to us when people were passionate enough to know how to hate and stupid enough to ignore the teaching of that inveterate troublemaker Paul, that “we wrestle not against flesh and blood but against principalities and powers.”

- Second, the enemies could be abstract: vice, ignorance, injustice – that sort of thing. That’s safely vague. Only scholars can be passionate about abstractions.

- The third and true possibility, of course, is that they have real, actual spiritual enemies: us.

- But if they no longer believe that, nor either of the other options, then the only possibility left is that there are no enemies, and no war, and no passion.

And that’s where we have them now. Ninety-nine out of a hundred of them never once in their lives get up from bed in the morning with the thought that the forthcoming day will involve a battle in the greatest war of all, and that their Commander is sending them on a mission only they can accomplish. Instead, they think of their planet not as a battlefield but as a bathtub.