So when they had gathered together, they began to ask him, “Lord, is this the time when you are restoring the kingdom to Israel?” He told them, “You are not permitted to know the times or periods that the Father has set by his own authority.”

– Acts 1:6-7

Jesus’ contemporaries just didn’t get what his goal was.

He came to be the Lamb of God, to take away the sin of the world (Jn 1:29), to seek and save the lost (Lk 19:10), to testify to the truth (Jn 18:37), to reconcile all things to God (Col. 1:20). Yet his followers kept expecting him to retake David’s throne, restore national Israel’s fortunes, kick out the Romans.

As a result, misunderstandings abounded. He had to keep telling the people he healed to keep quiet, lest their stories spread Messianic fervor. After he fed the 5,000, the crowds “were going to come and seize him by force to make him king” (Jn. 6:13). Jesus had to rebuke Peter (“Get behind me, Satan!”) when Peter thought that the Messiah couldn’t or couldn’t be allowed to die. James and John wanted to sit at Jesus’ right and left hands in what they thought was his immanent earthly kingdom. The crowd at the Triumphal Entry welcomed Jesus as the new king in Jerusalem. Peter tried to fight back when Jesus was arrested in Gethsemane.

And, even at Jesus’ ascension – even after the three years of traveling together alongside Jesus and hearing his instruction, after witnessing Jesus’ resurrection, after forty days with the resurrected Lord, during which “he opened their minds so they could understand the scriptures” (Lk. 24:45) – when he was on the verge of giving them their commission to spread the good news to the whole world and then returning to Heaven to be with the Father, they had to go and ruin the moment with yet another misunderstanding of his mission.

Lord, is this the time when you are restoring the kingdom to Israel?

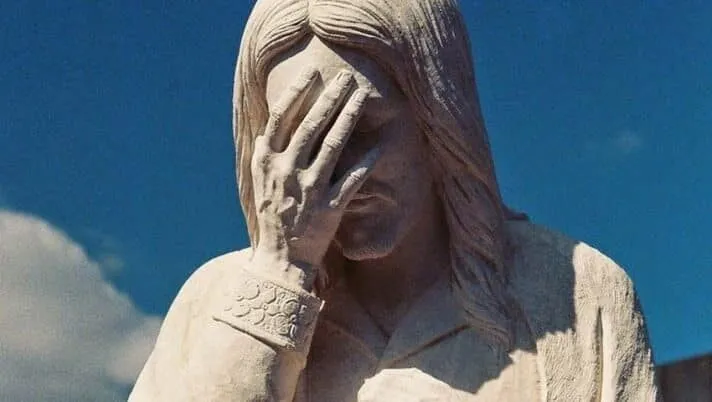

It’s a record-scratch moment; the kind of question that might prompt a facepalm, except that Jesus is too loving of a Shepherd to give in to that kind of exasperation with his sheep.

Ah, those silly disciples. Always thinking that Jesus’ job was to kick out the Romans.

I believe, though, that we’re too hard on Jesus’ disciples – they weren’t wrong, or, at least, they weren’t wrong in the way that we think they are.

They were Jews: so they knew they were part of God’s people, having been taught from infancy about the millennia of God’s dealings with them.

They knew in their bones that God had promised for centuries to care for them, to save them from their enemies, to give them a land, to make all things right, to give them a king and a priesthood who would faithfully follow God.

They knew that they had lost the land, had been driven into exile in the Babylon captivity, because of their sin.

They knew that, even though they had returned from captivity, they were in a sense still in exile – other than the relatively brief reign of the Hasmonean dynasty (starting after the Maccabean Revolt, c. 140 BC, and ending with Herod the Great’s ascension in 37 BC), the land was still not theirs, and so their sin must still be ongoing.

As N.T. Wright explains it,

The Jewish people have always believed that the God they worshipped was the one true God of all the earth; so what happened close up, in their own history, was seen to be of universal importance…

John [the Baptizer] didn’t mince words. The world is full of injustice: if there is a God, he must care about that; if he cares, he must do something about it; and since this was the lowest point of history as far as Israel was concerned, he must do something right here and right now…

Jesus went through Galilee, village by village, telling people that the kingdom of God was happening now. Now, at last, Israel’s oppression would be over. God would come home to save the people. Now, at last, with the world at its lowest point, evil would be defeated and justice would triumph…

Like the prophets of old, and like John the Baptizer himself, Jesus warned his contemporaries that when the kingdom of God arrived it would be a doubly revolutionary event. Yes, it would overturn all the power structures of the world; but it would also overturn all the expectations about how that would happen.

– N.T. Wright, The Original Jesus, p. 16, 29-30, 31, 32

Jesus’ disciples were right to look to God to keep his promises, to defeat their enemies, to save them from their sin and its consequences, to make things right. They simply didn’t set their expectations high enough, didn’t recognize who the greater enemy was. Because the sad history of Israel and Judah and humanity shows that, had Jesus merely kicked out the Romans, the problem of sin would remain, and judgment and exile would recur. It took a double revolution: the defeat of sin and death, rather than the oppressive empire; through love and sacrifice, rather than military conquest; led by God became flesh, as Prophet, Priest, and King, instead of a faithful human king and priesthood.

In fact, I believe we could learn something from the disciples: to know in our bones the millennia of God’s faithfulness to us, his people; to see behind our day-to-day lives to the great realities of sin and exile and salvation; to long for the day of the Lord to come, in eager expectation that God will act and evil will fail and justice triumph, instead of merely marking time waiting for the hereafter.

I think we’re too hard on Jesus’ disciples for another reason – because, even while we shake our heads at their impatient requests to restore the fortunes of Israel, we can be awfully wound up about God restoring the fortunes of America.

We’re told we need to take back America for God. Each successive election is pronounced “the most important of our lifetimes.” Politicians talk about how the other side will “hurt God” if “we” lose. (Christ’s Church can overcome the gates of Hades; is losing an election even a meaningful concept for it?) Religious organizations raise funds off of alarmist emails and mass mailings describing how dire our country’s situation is. As Russell Moore describes US politics, churches share “apocalyptic warnings that if these candidates weren’t elected, or these policies weren’t enacted, we would ‘lose our entire culture.’ But when those candidates lost, no one headed for the bunkers. The culture didn’t fall—at least not any more than it had before.” He’s narrating his perceptions of political struggles as a teenager in the 80s, but things haven’t changed.

Jesus’ gentle rebuke to his disciples – “You are not permitted to know the times or periods that the Father has set by his own authority” – applies to us too. I’m thankful for my country, and I care about what happens to it – but it will rise or fall according to God’s plan, and Christ’s Church will continue regardless of what happens to America. Instead of anxiously worrying about restoring the fortunes of a country, let’s continue to live out Christ’s instructions to his disciples:

But you will receive power when the Holy Spirit has come upon you, and you will be my witnesses in Jerusalem, and in all Judea and Samaria, and to the farthest parts of the earth.

– Acts 1:8