Like faith needs a doubt

Like a freeway out

I need your love– U2, “Hawkmoon 269”

Why do we need faith? If God is real, and if he’s (as generally accepted) powerful enough to do whatever he wants, then it would be simple for him to prove the reality of his existence. And yet, he doesn’t – many people don’t believe in God, or they don’t believe in this God, or they believe in God but doubt.

God could remove that with a snap of his fingers. Why doesn’t he?

A common answer in Christian circles is that because, if he did, we wouldn’t need faith. I’ve always found this answer unsatisfying. What makes faith superior, more valuable, more virtuous than knowledge? We wouldn’t accept this reasoning in human relationships.

“You never tell me you love me anymore!”

“You just need to have faith in me! If I told you I loved you more often, you wouldn’t need faith!”

You don’t have to be a licensed marriage and family therapist to know that wouldn’t make for a healthy relationship.

Surely God is better than that.

A second possible answer is that faith cannot exist without doubt – like in “Hawkmoon 269.” U2 isn’t necessarily trying to make a theological statement there – it’s just one of many images in a raw, passionate expression of Bono’s longing for his wife – but philosophers and thinkers have expressed variations of the idea throughout the centuries. Faith cannot exist without doubt; light needs darkness; we wouldn’t appreciate good unless bad also existed; and so on. This, to a Christian, is also unsatisfying. The idea that light cannot exist without darkness owes more to non-Christian dualism. In the Christian worldview, goodness is the ultimate reality, and evil exists only as (to quote C.S. Lewis in Mere Christianity) as “parasite” on it, “not an original thing.” He writes,

You can be good for the sake of goodness: you cannot be bad for the mere sake of badness. You can do a kind action when you were not feeling kind and when it gives you no pleasure, simply because kindness is right; but no one ever did a cruel action simply because cruelty is wrong – only because cruelty was pleasant or useful to him. In other words badness cannot succeed even in being bad in the same way in which goodness is good. Goodness is, so to speak, itself; badness is only spoiled goodness… The powers which enable evil to carry are powers given to it by goodness. All the things which enable a bad man to be effectively bad are in themselves good things – resolution, cleverness, good looks, existence itself.

Experiencing the bad may help us appreciate the good – a cold glass of water when thirsty, the relief of health after a bout of sickness – but that seems more a limitation of our finite gratitude and perception than some fundamental aspect of reality. To say that we can’t feel loved unless we’ve been abandoned, that we can’t enjoy a good meal unless we’ve faced starvation, that we can’t know faith unless we suffer doubt seems to shortchange the generous and perfect gifts coming down from our Father (James 1:17).

A more satisfying answer, to me, comes from the 19th century theologian and philosopher Søren Kierkegaard. He illustrates in his Philosophical Fragments by way of a parable:

Suppose then a king who loved a humble maiden… It was easy to realize his purpose. Every statesman feared his wrath and dared not breathe a word of displeasure; every foreign state trembled before his power, and dared not omit sending ambassadors with congratulations for the nuptials; no courtier groveling in the dust dared wound him, lest his own head be crushed… – Then there awoke in the heart of the king an anxious thought… Would she be happy in the life at his side? Would she be able to summon confidence enough never to remember what the king wished only to forget, that he was king and she had been a humble maiden? For if this memory were to waken in her soul, and like a favored lover sometimes steal her thoughts away from the king, luring her reflections into the seclusion of a secret grief; or if this memory sometimes passed through her soul like the shadow of death over the grave: where would then be the glory of their love?…

The king might have shown himself to the humble maiden in all the pomp of his power, causing the sun of his presence to rise over her cottage, shedding a glory over the scene, and making her forget herself in worshipful admiration. Alas, and this might have satisfied the maiden, but it could not satisfy the king, who desired not his own glorification but hers.

The solution, in Kierkegaard’s discussion – and here he shifts away from the parable to talk about the point – is for God to

become the equal of such a one, and so he will appear in the likeness of the humblest. But the humblest is one who must serve others, and the God will therefore appear in the form of a servant. But this servant-form is no mere outer garment, like the king’s beggar-cloak, which therefore flutters loosely about him and betrays the king… It is his true form and figure. For this is the unfathomable nature of love, that it desires equality with the beloved, not in jest merely, but in earnest and truth. And it is the omnipotence of the love which is so resolved that it is able to accomplish its purpose,

which the king could not do, because dressing as a beggar would be “a kind of deceit” for him.

The parable offers an answer to why God asks for faith and leaves room for doubt, rather than making everything clear and known. For God to clearly reveal himself would involve “all the pomp of his power, causing the sun of his presence to rise… shedding a glory over the scene.” God, out of love, wants us to freely choose to love him, and such a display would remove any element of choice. We would be cowed, overawed, left with no choice but to obey him.

Kierkegaard’s parable is a beautiful story, and it expresses deep truth about the nature of the incarnation and how Christ, being in very nature God, emptied himself (Phil. 2:8). But, as an answer to the dilemma of faith versus knowledge, it may be more calibrated to our modern era than the Bible’s view. Modernity talks about the hiddenness of God or even the death of God, and scientific naturalism offers an intellectual justification for atheism. The Bible, on the other hand, seems to assume a much clearer state of affairs. There are times when Scriptures express doubt, such as Psalm 44:23-24:

Rouse yourself! Why do you sleep, O Lord?

Wake up! Do not reject us forever.

Why do you look the other way,

and ignore the way we are oppressed and mistreated?

Or Psalm 22:1-2:

My God, my God, why have you abandoned me?

I groan in prayer, but help seems far away.

My God, I cry out during the day,

but you do not answer,

and during the night my prayers do not let up.

Or Psalm 10:1,11:

Why, Lord, do you stand far off?

Why do you pay no attention during times of trouble?

The wicked man says to himself,

“God overlooks it;

he does not pay attention;

he never notices.”

And passages such as Matthew 13:24-30, 2 Peter 3:8-10, and (more obscurely) Romans 11:25-32 suggest that God restrains himself out of a desire to give people opportunity to come to him. But the Bible’s more common tone reflects a baseline assumption that God is real. For example, Psalm 19:1-2:

The heavens declare the glory of God;

the sky displays his handiwork.

Day after day it speaks out;

night after night it reveals his greatness.

Or Romans 1:19-20:

What can be known about God is plain to them, because God has made it plain to them. For since the creation of the world his invisible attributes—his eternal power and divine nature—have been clearly seen, because they are understood through what has been made. So people are without excuse.

How do we square this settled confidence in the existence, power, and goodness of God with our own experiences of doubt in the midst of faith?

Part of the answer involves looking closer at the nature of knowledge itself. What’s required to know something beyond a shadow of a doubt? The answer is surprisingly difficult. The past several years have seen prolonged, contentious debates over what should be simple factual matters: Where was Barrack Obama born? What medications and precautions are effective against Covid? Who won the 2020 election? Even attempting to definitively answer one of these questions could lead down a rabbit hole of state birth certificate record-keeping practices, clinical trial methodology and interpretation, mRNA technology, voting machine design and manufacture, and more. If straightforward factual questions are this challenging, then how we can expect questions about ultimate reality, the origins of the universe, or morality and ethics to be any easier?

There’s an old proverb, “A fool can ask more questions in an hour than a wise man can answer in seven years.” Cardinal John Henry Newman in 1851 wrote of the difficulty of responding to attacks on Catholicism; someone attempting to answer criticism of some historical church figure

finds himself at once in an untold labyrinth of embarrassments… He goes to his maps, gazetteers, guidebooks, travels, histories;—soon a perplexity arises about the dates: are his editions recent enough for his purpose? do their historical notices go far enough back? Well, after a great deal of trouble, after writing about to friends, consulting libraries, and comparing statements, let us suppose him to prove most conclusively the utter absurdity of the slanderous story, and to bring out a lucid, powerful, and unanswerable reply; who cares for it by that time? who cares for the story itself? it has done its work; time stops for no man; it has created or deepened the impression in the minds of its hearers that a monk commits murder or adultery as readily as he eats his dinner. Men forget the process by which they receive it, but there it is, clear and indelible. Or supposing they recollect the particular slander ever so well, still they have no taste or stomach for entering into a long controversy about it; their mind is already made up; they have formed their views; the author they have trusted may, indeed, have been inaccurate in some of his details; it can be nothing more.

One of the paradoxes of our age is that, although modern technology has given us far more accessible and comprehensive resources than Newman’s “maps, gazetteers, guidebooks, travels, histories,” our minds aren’t any more capable; in fact, the torrent of conflicting viewpoints and cherry-picked facts wash over us, leaving us capable of no more than Newman’s “clear and indelible” “impressions.”

In spite of this, most of us muddle through everyday life: we reach conclusions about politics, health care, and current events, without being plagued by doubts and uncertainties as to whether our opinions on the issue du jour might be incorrect. I might wish that some people had a little more doubt (there are strange and frustrating opinions out there), but in general, this is a sign of mental health: we have finite time and energy and no shortage of worthwhile things we could be doing, and it’s impossible to apply the diligence that Newman describes to every issue of the day, so we satisfice: we do good enough to get enough confidence to move on with our lives.

Can we do the same with God? It’s harder, at least. The questions run much deeper; the uncertainties risk touching the core of our being; the stakes are infinitely higher.

We are, at this point, getting closer to the nature of our doubts. Because not only is knowledge beyond a shadow of a doubt surprisingly hard; there are actually two kinds of knowledge. “I know that 2 + 2 = 4” and “I know that the earth revolves around the sun” are rational knowledge: comprehended with reason, verifiable or falsifiable with the right training, methodology, and equipment. Other spheres of knowledge (“I know that Abe Lincoln was president”) are less obvious but still fall under this category: they can’t be directly inspected but can still be grasped through historical study and scholarly consensus.

What about, “I know my parents love me”?

Or, “I know my friend Jack is trustworthy”?

Or, “I know I’m doing right by my kids”?

These are relational knowledge: comprehended with emotion as well as reason, dependent on others’ hearts and minds as much as our own grasp of observable reality. It’s impossible to ever have perfect certainty: there’s no way to prove that your parents don’t harbor secret resentment, that Jack isn’t plotting some cruel betrayal, that your kid isn’t leading a double life. It’s a realm of story as much as facts: a relationship is built, not of objective and quantifiable characteristics, but as the story of the sum of interactions, of time together and affirmations and gestures of concern and increasing self-disclosure and challenges successfully navigated. I know that my wife loves me, not because I found the methodology and equipment to verify it, but because of the story of our whirlwind courtship, the heady honeymoon days, raising children together. Of the countless hours in conversation, the gestures of love seen in a thoughtful purchase or act of service, the commitment to each other in good times and bad.

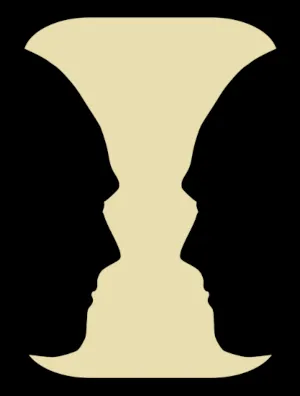

But the nature of story is that it can shift, be reinterpreted, have plot twists. What happens if I start to tell myself a different story: that the courtship and honeymoon were just infatuation, that raising children does not make a marriage, that the conversations are no longer meaningful, that the neglects and disappointments we give each other are truer than the gestures of love, that the bad times eclipse the good? Like staring at an optical illusion, the story of the relationship inverts, and doubt creeps in.

How do you doubt-proof a relationship? By continuing in it: by continuing the time together and affirmations and gestures of concern and self-disclosure that made it in the first place. In other words, by remaining faithful.

Part of the issue is that we confuse ourselves on the meaning of “faith.” We tend to equate it with belief, and, as Westerners and heirs of the Age of Enlightenment, interpret that as belief in a set of facts. And, certainly, that’s a key part of Christianity. “The one who approaches God must believe that he exists and that he rewards those who seek him” (Heb. 11:6). Our religion is grounded in the belief “that Christ died for our sins according to the scriptures, and that he was buried, and that he was raised on the third day according to the scriptures, and that he appeared to Cephas, then to the twelve. Then he appeared to more than 500 of the brothers and sisters at one time, most of whom are still alive, though some have fallen asleep. Then he appeared to James, then to all the apostles” (1 Cor 15:3-7), and now he makes himself known to us also.

But faith is not just belief in ideas. It also means belief in a person – not mere confidence in their reliability (as in the “trust falls” of cheesy team-building exercises) but commitment and allegiance. Faithfulness to a marriage entails a commitment to remain in, nourish, and grow in that covenant relationship, even when it’s costly. Faith in God entails committing to him, in ways that cost us something, in response to his faithfulness to us, even when it cost him the cross.

Our doubts in God often play into this double meaning of faith. The Psalms cited above question more whether God cares than whether he exists. C.S. Lewis wrote of his pre-Christian life, “I was at this time living, like so many Atheists or Antitheists, in a whirl of contradictions. I maintained that God did not exist. I was also very angry with God for not existing.” In my own struggles with doubt, there was an intellectual component – the facts of the universe and existence and history shifted, optical-illusion style, until the story of atheism at times seemed to make more sense than the story of Christianity. But there was also a relational aspect – if God is real, powerful, and good, why isn’t he doing what I expect? Why is parenting, marriage, morality – life as a whole – so hard? The latter fed the former; I can’t imagine that I would have seen an optical-illusion shift in the facts if I weren’t struggling to trust God the Person.

How do you doubt-proof that relationship? Certainly, as we remain faithful to God, as we read his Word and spend time with his family and experience his goodness, we strengthen our trust in him and our commitment to him. But I’m not certain that it’s even theoretically possible to remove all doubt. The only way I can imagine is for God to simply overpower us with a demonstration, to come like Kierkegaard’s king “in all the pomp of his power, causing the sun of his presence to rise over [our] cottage[s].” The Bible tells us that this will happen: Jesus Christ will “return with the clouds, and every eye will see him” (Rev. 1:7), and “every knee will bow – in heaven and on earth and under the earth – and every tongue confess that Jesus Christ is Lord” (Phil. 2:10-11), and we will join in “the banquet at the wedding celebration of the Lamb” (Rev. 19:9). As C.S. Lewis describes in Mere Christianity,

God is going to invade, all right: but what is the good of saying you are on His side then, when you see the whole natural universe melting away like a dream and something else – something it never enters your head to conceive – comes crashing in; something so beautiful to some of us and so terrible to others that none of us will have any choice left? For this time it will be God without disguise; something so overwhelming that it will strike either irresistible love or irresistible horror into every creature. It will be too late then to choose your side. There is no use saying you choose to lie down when it has become impossible to stand up. That will not be the time for choosing: it will be the time when we discover which side we have really chosen.

But it has not happened yet. I’ve used the analogy of marriage, but we, God’s bride, are still awaiting the wedding. On this earth, while we’re not yet perfected, it seems that U2’s “like faith needs a doubt” is more profound than I realized; doubt may be inseparable from faith after all.

In Yearning for the Undeniable God, Brant Hansen writes:

Here, and now, I’m convinced there’s not a thing God could communicate to you that you can’t deny. Nothing He could say would be incontrovertible. And no matter what He did, what miracle He showed you…? You could rebel against it. This is the reality of where we are, now…

You want something that makes it impossible for you to doubt. Problem is, you’re human, and humans can doubt anything. The clear voice of God, itself, can be doubted. (“Was that really Him, really?” “Couldn’t that have been a neural misfire?” “You know, maybe that ‘miracle’ years ago was a coincidence…”)

You want something you can’t have… yet.

But now… the good news:…

If you want more of God, you’re going to yearn. And yearning isn’t bad. Yearning happens when you are in love. Lovers yearn, when they want, but they cannot fully have. Not yet…

Want to experience yearning in another context? Try being engaged to be married, but living a chaste life. I’ve done it. It’s hard. You yearn, and you know what you want, and you know you’re going to get what you want… but not yet. You want more… but not yet.

It’s really, really tough. And, tough as it is, it’s really, really good. Yearning like that – that powerful – only happens because the object of the yearning is that powerful.

And let’s face it. I said “yearning in another context”, but you know what? It’s really not another context: We are promised, in the end, a wedding. Jesus will have His bride, and it’s His people. And He will know us, and we will know Him, fully. Paul wrote as much: “Then I shall know just as I also am known.”

So you’re yearning, and so are we all, but it’s building up to something. Something really, really good.

You’re engaged, and the wedding is going to one amazing party, and knowing God, finally, and truly, is going to be worth it.

“You never tell me you love me anymore!”

“I do. I’ve told you and shown you in the past, but I know that it can be easy to forget. I give you gifts, but sometimes you overlook them or take them for granted. I tell you, but you don’t always hear me. Please hear me: I love you. I know this isn’t the answer you wanted, but please trust me that it’s for your best.”

A licensed marriage and family therapist wouldn’t recommend this for an equal partnership of husband and wife, but for a Father and child, it may be just right.