Occasionally a Bible verse seems so relevant to some current situation that it hits you between the eyes. So it was for me with Leviticus 19:34, in light of the current debates around immigration enforcement:

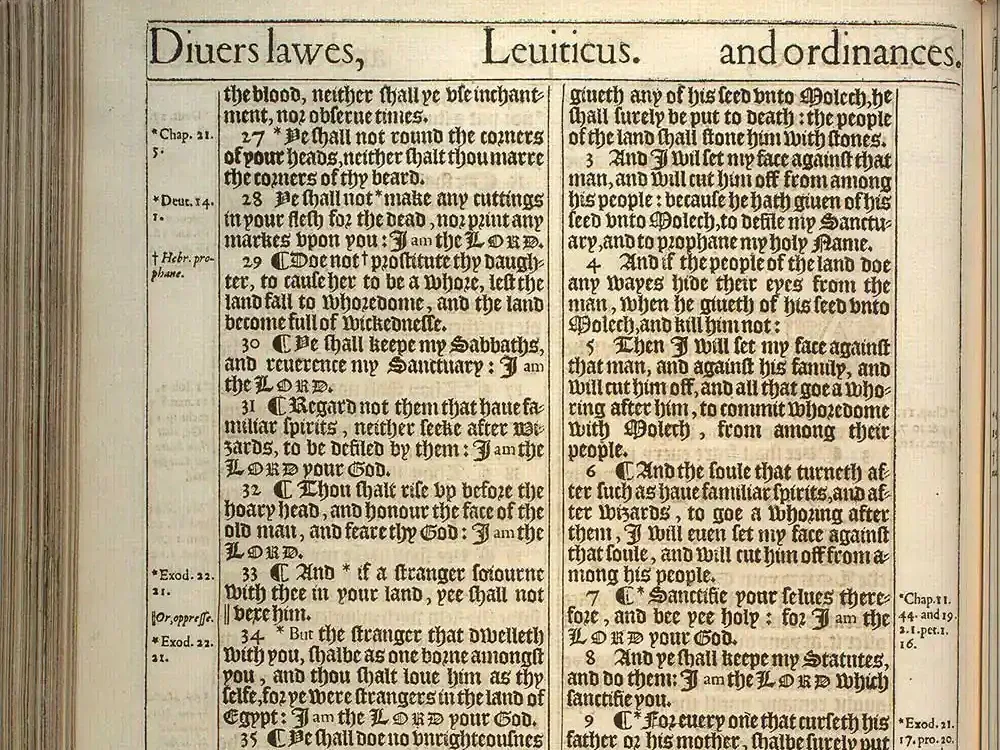

The resident foreigner who lives with you must be to you as a native citizen among you; so you must love the foreigner as yourself, because you were foreigners in the land of Egypt. I am the Lord your God.

But why did Leviticus spell that out? And does it resolve any questions?

You could argue that we don’t really need it. Jesus says that the Law and the Prophets are summed up in the commandments to “Love the Lord your God with all your heart, soul, mind, and strength” and to “Love your neighbor as yourself.” “Love your neighbor” was not a new command, and someone living with you is, obviously, your neighbor (even without the radical redefinition of the Good Samaritan). So maybe it’s redundant.

For that matter, maybe we don’t really need “Love your neighbor as yourself.” Jesus’ questioner only asked for one greatest commandment, so Jesus could have stopped with “Love the Lord your God with all your heart, soul, mind, and strength.” If we love the Lord, then we’ll try to do as he wants, and if we love God, we’ll love those made in his image, so maybe “Love your neighbor” could go without saying. I’m not sure if Jesus’ insistence on including it anyway says more about us (he knows our tendency to turn religion into a personal, interior thing that fails to impact how we relate to others) or him (that in the mind of Christ it’s impossible to separate loving God from loving whom he loves, that we’re created for both communion with God and also community with each other, that drawing closer to him inevitably draws us closer to each other).

And so it seems that just being told to love God isn’t enough. Otherwise, we forget and make our religion that personal, interior thing. And just being told to love our neighbors isn’t enough, because we start trying to wriggle out of it: “Who is my neighbor? How many times do I have to forgive him? Tell me the requirements so I can know when I’ve fulfilled them and need go no farther.” Jesus tells a whole parable to redefine “neighbor” as everyone you come into contact with – not just that, but everyone you can be a neighbor to. (In other words, he could have responded to his questioner with a definition: “Your neighbor is whoever you meet, even if they’re a member of a hated ethnoreligious group.” He instead responds with a command, “Go and do the same.” Be a neighbor to others.)

And, even with the example of the Good Samaritan, being told to love our neighbors isn’t enough. The disciples wanted to exclude someone outside their immediate circle. No, Jesus said, he’s for us. James’ recipients wanted to exclude based on poverty. No, James said, love without favoritism. The Corinthians wanted to split into factions. No, Paul said, be united. Roman Christians wanted to judge each other on secondary religious practices. No, Paul said, act in love and build each other up. The Israelites were tempted to mistreat foreigners. No, Moses says, love them as yourself.

It’s like we’re wired to look for ways to divide. To exclude. To push others down in hopes of maybe securing a little bit better position for ourselves. Or at best just to ignore, to pretend they don’t exist so they don’t make demands on us. In Searching for God Knows What, Donald Miller writes,

When I was a kid in elementary school my teacher, Mrs. Wunch, asked our class a question I’ve come back to about a million times…

“If there were a lifeboat adrift at sea, and in the lifeboat were a male lawyer, a female doctor, a crippled child, a stay-at-home mom, and a garbageman, and one person had to be thrown overboard to save the others, which person would we choose?”

I don’t remember which person we threw out of the boat. I think it came down to the lawyer, but I can’t remember exactly. I do remember, however, that the class did not hesitate in deciding who had value and who didn’t. The idea that all people are equal never came up… We knew this sort of thing intrinsically. Or at least we thought we did. (p. 105, emphasis added)

Excluding, neglecting, or opposing those outside our circles, the poor, other church factions, fellow believers with different practices, members of other ethnic or religious groups, foreigners. Drawing lines to say who’s our neighbor and who isn’t. It’s all what Miller terms lifeboat thinking. In a fallen, finite world, we look for ways to band together in a tribe, a group that will have our backs and will help us out-compete the other tribes for survival, who’ll help us shove someone else out of the lifeboat if need be so our position can be secure. We fall into zero-sum thinking, believing that someone else having more means we’re left with less. Against that, God tells us, “I have everything, I take care of everything, and I’ll take care of you too. So stop worrying about yourself and love your neighbor as you love yourself.”

Immigration and immigration enforcement is currently a topic of vehement political debate in the US. I expect that some variation of “Love your neighbor” shows up on at least one sign in almost 100% of immigration rallies and protests. I expect that it’s convincing to roughly 0% of people. After all, immigration policy is a complex topic, and quoting a few Bible verses doesn’t easily resolve all the issues involved. God’s promise to meet our needs does not, it seems, extend to empowering us to do everything that might help everyone in the world – or even within our hemisphere or our borders. No one would argue that loving your neighbor means we cannot enforce the laws. (In fact, enforcing the law – preserving and promoting order – may be the most loving thing that an authority can do.) We’re commanded to love our enemy, but, outside of pacifists (whom I greatly respect but disagree with), Christians recognize that loving your enemy is compatible with punishing and, perhaps, even killing them. (C.S. Lewis wrote, “I have often thought to myself how it would have been if, when I served in the First World War, I and some young German had killed each other simultaneously and found ourselves together a moment after death. I cannot imagine that either of us would have felt any resentment or even any embarrassment. I think we might have laughed over it” (Mere Christianity, p. 119)). There aren’t easy answers.

Immigration policy in Moses’ day was a complex topic. The Hebrew term for resident foreigner, ger (גֵּר), has a range of meaning in different contexts. In Genesis, ger refers to the patriarchs, known and respected inhabitants of Canaan who didn’t acquire land or stakes of their own. In the Law, it seems to refer to full converts to the worship of Yahweh, participating in the covenant and Passover. (Because God has always desired to call a people to himself and to bless the world through his people, he provided a way even in the days of ethnic Israel for others to join and participate in his covenant.) As ethnic minorities, the ger were members of a vulnerable class, so the Law repeatedly singled them out for special protection, along with widows and orphans (Ex. 22:21; Deut. 24:14, 17; 27:19). In the Septuagint, ger is usually translated as “proselyte,” emphasizing their religious rather than national status. But Leviticus 19:34 also applies ger to the Israelites living in Egypt – residents of a racial enclave at best, victims of slavery and genocide at worst. God gives the mistreatment that they suffered in Egypt as the reason why they should never mistreat someone else.

How do we apply “loving the foreigner as yourself” today? It’s a complex topic. The word doesn’t even translate well; in English, “foreigner” is typically understood to mean someone whose primary allegiance remains to another country – a temporary or long-term resident but not an immigrant. The ger of Leviticus 19:43 seems more like an immigrant and naturalized citizen (of lesser social status by Israelite standards, but still accepted and protected in a way that many ancient societies would have perhaps resisted). As a nation of immigrants, we often pride ourselves on treating naturalized citizens as full Americans. In ancient Israel, it could take generations for a ger to be fully accepted. How does “foreigner,” “ger,” “immigrant” apply to someone like Kilmar Abrego Garcia, who committed a misdemeanor offense in entering the country, has (contested and unclear) accusations of gang membership, and started a family in Maryland? Denied asylum, he was instead granted a withholding from removal, leaving him in some sort of near-limbo where he can’t be legally returned to his homeland but could be deported at any moment if the US finds a country willing to take him (maybe Uganda). Our laws and due process try to make sense of this, but few of us have the requisite backgrounds to do so, and our attempts may end up saying more about our own biases than the facts of the situation. Even our Yale Law-trained vice president, it seems, gets it wrong.

The cultural changes and language applicability are complex, and we can legitimately come to different conclusions about the best way to resolve them, but the principles are clear. “You [Israelites] were foreigners in the land of Egypt:” so don’t mistreat anyone else as you were mistreated. It’s easy give in to lifeboat thinking and mistreat or exclude foreigners and immigrants: don’t. We Americans were immigrants: treat others as we want to be treated. Once we Christians were not a people: now we are, and we can love others regardless of their peoples. “I am the Lord your God.” Love, then figure out the policies.

Jewish relations with Samaritans were a complex topic. Differences had existed ever since the fall of the northern kingdom of Israel in 722 BC and the subsequent deportations, relocations, and intermarriages by the Assyrian empire. Jews and Samaritans had significant religious differences: the Samaritans had their own version of the Torah, their own temple on Mount Gerizim, and their own explanations of their split with Judaism. (Rather than attributing their origin to Assyrian resettlement, they blamed Samuel’s foster father Eli as a schismatic priest who led the Jews astray in breaking away from proper worship.) The most immediate cause for hostility was when John Hyrcanus, Maccabean leader and high priest of the Jews, destroyed the Samaritan temple at Mount Gerizim, devastated their land, enslaved them, and attempted forced conversions, around 110 BC. Trace the history back far enough before John Hyrcanus and Assyrians and you’ll encounter northern Israel’s rebellion against the divinely anointed David king over taxation and forced labor; centuries of occasional war and raiding and sometimes alliances.

The Samaritan of Jesus’ parable who saw the robbery victim didn’t attempt to resolve any of this. The most obvious reason is that this wasn’t the point: as a master storyteller, Jesus arranged the story to make his point about being a neighbor with as vivid and impactful an example as possible, without getting bogged down in every potential detail and nuance of the tale. But there’s a simple in-story reason as well: the sordid history of grievances and conflicts didn’t matter when the Samaritan could look at the bloodied, naked, dying man in front of him and say, “This, right here, is not right. I can do something about it.”

So much, right here, is not right. We may not know the right answer to immigration policy, but we can say that lying, dehumanizing, terrorizing, finding delight in others’ suffering, separating families, racism, cruelty (including to children), and lawbreaking are wrong. We can ensure that even those we detain or send to prison are treated humanely – that is, with love. We can take seriously the government’s duty to maintain order by prioritizing criminals over those who are merely easy to apprehend. We may not know the right answer to Israeli-Palestenian relations, but there, too, we can say that 1,200 dead and 65,000 dead are both wrong, that both Israelis and Palestinians should be able to live in freedom and security.

So many voices in the world make this hard. They want to exclude, to divide into tribes, to say that if you’re not for them then you’re for the enemy – to reduce everything to a binary choice. But that’s zero-sum lifeboat thinking again. The Bible teaches that there is a binary, but the dividing line often isn’t where we think. Whoever isn’t against us is for us, but whoever is not with Christ is against him. The line includes some of the worst sinners and outcasts while excluding many of the most religious. It breaks down our deepest divisions while separating father from son and mother from daughter. The binary line between good and evil ultimately runs, as Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn says, “not through states, nor between classes, nor between political parties either – but right through every human heart.” To remember this, we need to immerse ourselves in Christian community, in disciplines such as prayer and Scripture, to be spiritually formed into the kinds of people who won’t be squeezed into the world’s lifeboat thinking. Look for neighbors. Be a neighbor. Look for ways to love others.

The other famous Samaritan story is the woman at the well. There, too, Jesus doesn’t attempt to resolve Jewish-Samaritan relations. The woman tries to engage him on the topic of the long-destroyed temple at Mt. Gerizim, but he redirects to something better: Spirit. Truth. Himself.