I got a new book.

It’s short – 28 pages, barely long enough to have a proper binding. Self-published. It’s not available on Amazon, not listed on Goodreads; it’s almost impossible to find any mention of it on Google. It describes itself as a children’s book, and, with double-spaced text and amateur black-and-white illustrations, it could pass as an early reader, but its writing style and vocabulary occasionally forget that. It will never be a best seller, never win any awards, never go viral. It will not shape the popular discourse, revolutionize people’s understandings, or be studied by future generations.

Of the hundreds of books I own, it’s one of my most special.

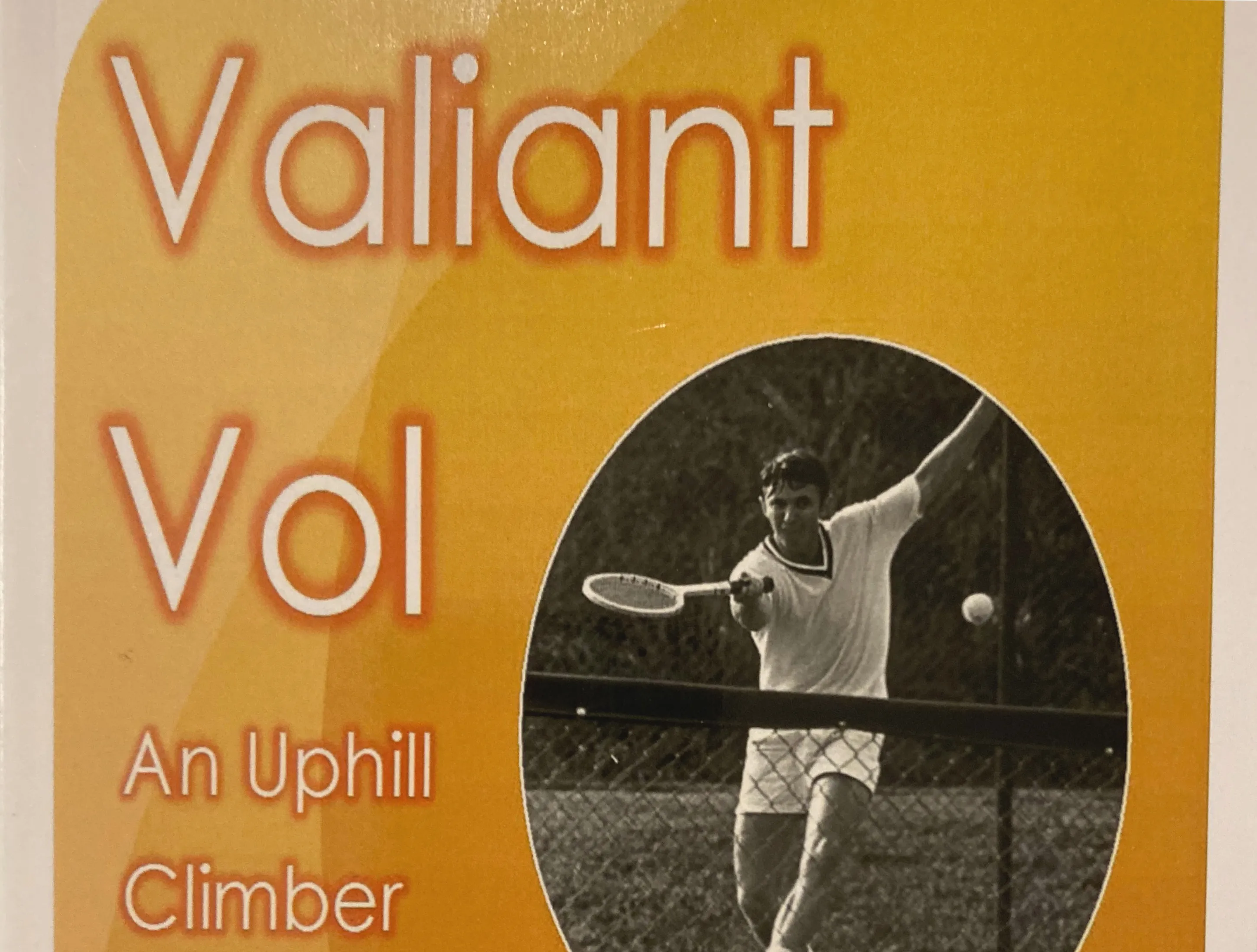

The book is Valiant Vol, An Uphill Climber, by Sam Darden. I met Sam when I was in graduate school, when he was the campus minister at the Christian Student Fellowship (CSF) at the University of Tennessee. His book tells of his childhood and youth; he grew up in an athletic family, loved sports, and dreamed of playing basketball, but his body didn’t cooperate. A weakness in his bones meant that he repeatedly suffered from broken legs, five times in each femur, in the same spot each time. Breaks were followed by surgery, rods and pins, recovery and crutches. Sam was for a while angry at God, but he found a new outlet for his athletics: he started playing tennis, practicing whenever he wasn’t on crutches. At UT, he joined the tennis team, was elected team captain, and won a Southeastern Conference (SEC) Doubles Championship. He concludes,

I believe it [my story] is about a God who loved me, healed my broken bones, encouraged, and allowed me to play a sport I loved. It is about a God who guided me to become the person He created me to be… Sports were not taken completely away from me, but I believe it was limited, so another path could be taken.

And, after he got to follow his dreams of college athletics, he entered the ministry, serving with his wife Kathy at the CSF for 38 years. He writes, “This has been a main purpose for our lives, one that went beyond any athletic or other honor we could have imagined. I believe God directed us to a wonderful life beyond our dreams” (emphasis in original).

When I met Sam, one of my favorite Christian bands, The Waiting, had just come out with a new album, Unfazed. In the last song on the CD, “Too Many Miles,” they sing,

Too many miles straying from Your side

Failing to fit in Your shoes

Too many miles trying to run and hide

When there was so much to lose

Break my leg if You must

But keep me close to You

Sam would, I think, say that this was done literally in his case. Even in his fifties, with years in the ministry to help mellow him out, he could still be intensely competitive – carefully planning a winning strategy for whatever silly relay race we’d organized for a campus event, pairing himself with the absolute worst Ping-Pong player in the group to handicap his superior skill and then still going all-out to win, and so on. He once said that his athletics would have turned into an idol and his competitiveness would have pulled him away from God, had God not used his ailments to redirect his life.

It’s a powerful, poignant story, but it’s not the reason that Sam’s book is so special to me. Rather, it’s what Sam meant in my life. He gave me a physical and spiritual home during grad school. He taught me about the gift of the church. He modeled faithfulness in how he and Kathy dealt with her health problems, their son’s death in a car accident years earlier, back pain, unanswered prayer. He encouraged me to be an adult, to live and serve within a church, instead of perpetually holding back and assuming those older and wiser would take care of things.

And that’s just what he did for me, and I was one of hundreds of students who passed through the doors of the CSF during Sam and Kathy’s 38-year ministry.

In an age of livestreamed services, streaming media, two-day shipping on millions of books, two thousand years of church history, and the evangelical industrial complex, I sometimes wonder about the role of the local church. If the world’s resources are at my fingertips, how can a local church compete? Why listen to the local preacher when Andy Stanley and David Platt are more eloquent? Few worship bands have the talent or production values of Hillsong United or Bethel Music. Why spend the effort to lead a Bible study or small group when RightNow Media has 25,000 videos that can cover the same content deeper, more professionally, from more perspectives? Sam’s story is powerful, but so are George Müller’s, Eric Little’s, Joni Erickson Tada’s, Jim Elliot’s; what can he add? We have the scholarship and insights and teachings of writers from Augustine to Brother Lawrence to C.S. Lewis to Tim Keller, with millions of dollars of Christian books sold each year; what can any lone writer or teacher hope to add to that?

Sam gives me part of the answer to this question. His book may not have the eloquence of C.S. Lewis or the scholarship of N.T. Wright, but his book to me is not just a book: it’s a representation of a life poured into me and others. As Sam told the gathered CSF alumni at a reunion, “You are our legacy.” My discouraging ruminations over the contributions of the local church make the mistake of assuming that the content is all that matters – the ideas, the presentation, the technique, as if Christianity were simply a matter of learning the right concepts in the right way. But it isn’t – it’s learning a lifestyle of following Christ, learning to live in fellowship with each other, by receiving this legacy of faithfulness from the parents and grandparents and ministers and teachers and mentors who’ve gone before us, and passing on this legacy to the children and grandchildren and churchgoers and learners who come after us.

I once read about a preacher, discouraged that some young men had stopped attending church in person in favor of watching sermons from some celebrity paster online. “Why?” the preacher asked.

“Because this guy tells it like it is!” they replied. “He gets in our grill!”

But I can get in their grill too, the preacher thought, because I know them.

I’m immensely thankful for the resources that our church history and our modern technology and prosperity allow. But there’s no substitute for living out our faith in person, sharing our whole lives with others, instead of merely consuming the best content possible. Jared C. Wilson writes that hearing a sermon from someone who doesn’t know you “isn’t the same… in the same way that hearing a stirring word from a role model isn’t the same as hearing a stirring word from your dad.” An unschooled amateur who knows and loves, who pours out their life, who can be seen and emulated, can have a deeper impact than Lewis or Spurgeon or Keller.

It’s hard to find a more influential Christian writer than Paul of Tarsus. But Paul himself recognized the limits of writing:

You yourselves are our letter, written on our hearts, known and read by everyone, revealing that you are a letter of Christ, delivered by us, written not with ink but by the Spirit of the living God, not on stone tablets but on tablets of human hearts. (2 Cor 3:2-3)

Richard Hays explains, “in the new covenant incarnation eclipses inscription,” “center[ing] not on texts but on the Spirit-empowered transformation of human community.”

And John, the most prolific New Testament author after Paul and Luke, sought to interact with his beloved brothers and sisters in person. He concludes his second letter,

Though I have many other things to write to you, I do not want to do so with paper and ink, but I hope to come visit you and speak face to face, so that our joy may be complete. (2 John 12)